The film does a phenomenal job of marshaling all its techniques towards this sense of constant movement, enough so that even during the dialogue scenes, things are being kept moving. Alongside this, there's a thrumming techno score by James Shimoji that insistently, loudly pushes all of the racing sequences ahead with a constant rhythmic throb.

#Redline anime movie theatre screening drivers#

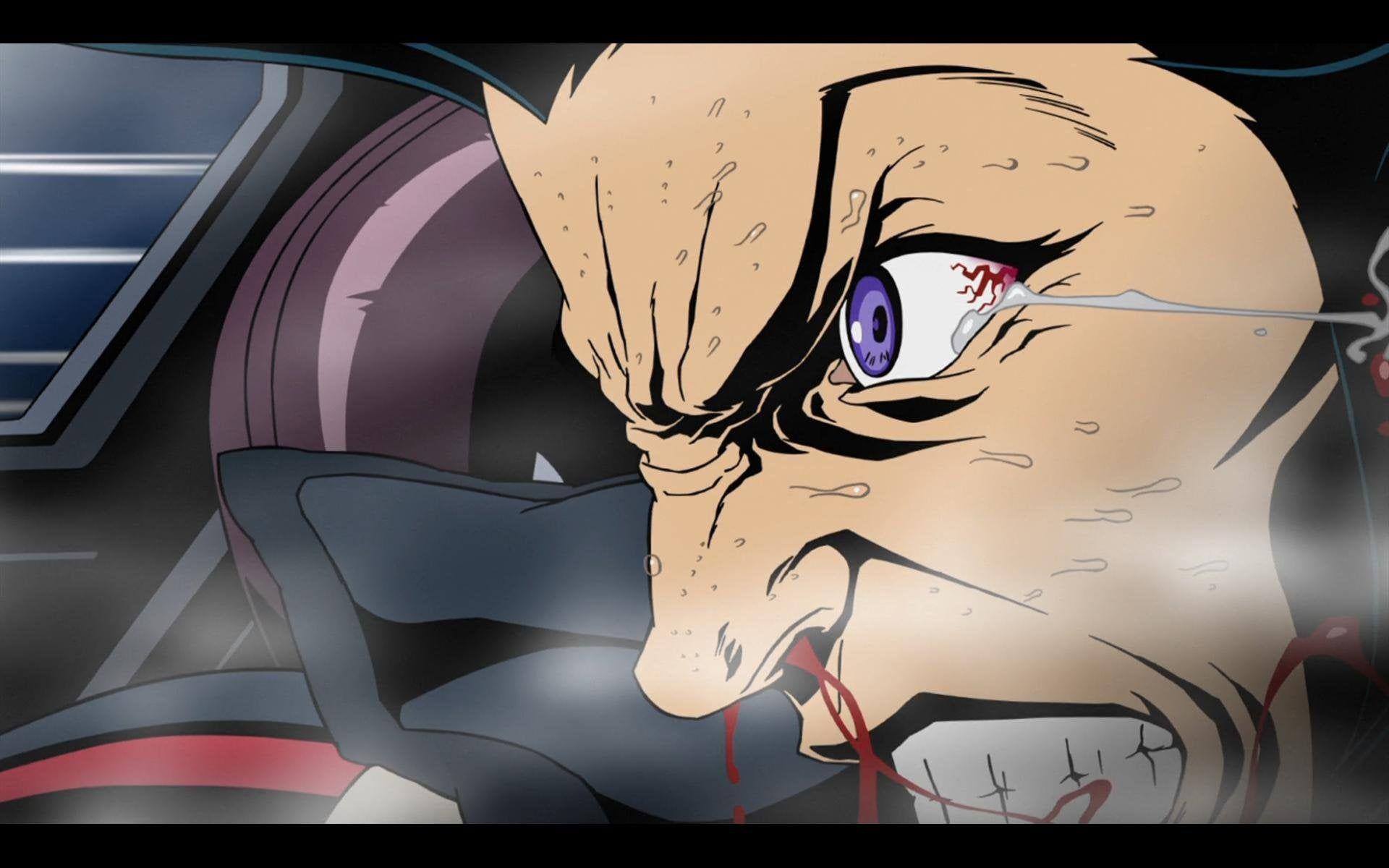

It's an environment and a scenario perfectly designed to take advantage of animation, and director Koike Takeshi - making his feature debut, after an admirable career as an animator, as well as directing the pilot for Afro Samurai and a sequence in The Animatrix - goes all-in on letting his drivers fly around space in flagrantly impossible ways, while leaping from close-ups to wide shots and back with abandon, but always preserving the sense that every part of the frame is in constant motion.

#Redline anime movie theatre screening full#

The competitors are a wide array of humans and aliens, the vehicles range from hovercraft that transform into dancing robots all the way to our protagonist, driving a gold-colored Trans Am, and the race sequences take full advantage of the different kinds of movement that all this can permit, laid atop an alien robot planet full of desolate grey plains and shiny dark metallic surfaces. It's not just that it's brightly colored and fast-moving, but that the fast movement keeps bringing new colors in, constantly demanding our eyes re-adjust to new stimuli and never giving them enough time to actually do so.Īll of this is in service to a story about the distant future, in which a galaxy-spanning race network is holding its every-five-years championship race, the Redline. It is overwhelming in every way a film can be visually and sonically overwhelming. With Redline, the startling mix of color, flatness, and fluid movement - I don't want to harp on it, but this is extraordinarily smooth for Japanese animation, especially in the effects-heavy sequences (and this is a film with a lot of effects) - is all in service to creating something wild and excessive, a movie that isn't merely going over the edge, but wants us to be constantly aware of how far out we're dangling. Every one of those is newer than Redline, and to a certain extent, every one of them is "tamer". There's an exceedingly short list of films that combine these techniques in such a bravura way that I'd be ready to compare this to: The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, The Red Turtle, The Girl Without Hands, Lu Over the Wall. This is as good an example as I can name of the productive and healthy relationship between different animation techniques: every frame was hand-drawn (around 100,000 drawings in total, according to the press releases at the time, a substantial number for a 102-minute animated feature), and so we get the fluidity and flexibility of traditional animation, but it has a sleek, futuristic cleanliness that could only have been achieved by using the stability of computer painting. Though even throwing around a term like "pop art" doesn't at all get at how strongly the hyper-saturated colors seem to glow off the screen. If Roy Lichtenstein designed the covers for Amazing Stories, using computer painting style and the character design ethos of Japanese animation, and the whole thing was in constant movement, that's getting us pretty close to the vibe of the thing.

The film's style feels like it should be easier to pin down than it is there's a clear indebtedness to '60s pop art and '90s and '00s digitally-colored comics in the bold swatches of strong colors, and the deep, solid blacks that define the shapes of faces and spaces.

Hyperbole is a dangerous thing, but even so, Redline is one of the most striking-looking animated movies I have ever seen.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)